Contents

Why Now

The Scope of this Work

Mapping the Threat Landscape

A working taxonomy of AI risks

Some examples of how risks are already showing themselves

How is Civil Society Currently Responding? Mapping the Movement

Protest, disruption and public mobilisation

Narrative shaping and watchdogs

Public literacy and democratic engagement

Infrastructure, field building and political lobbying

Observations and Propositions from the Map

Conclusion

About Social Change Lab

Cover image by Elise Racine: https://betterimagesofai.org

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is reshaping our world at unprecedented speed. Harms caused by AI systems are already highly visible, with real impacts on individuals, societies, and institutions. And the technology is continuing to advance at a breakneck pace. Alongside is growing unease that we are at risk of amplifying and accelerating existing harms as well as adding new ones as we hurtle into even more dangerous, uncharted territory.

The world’s leading AI labs openly acknowledge that they are pursuing artificial general intelligence (AGI) which many experts believe will be closely followed by artificial super intelligence (ASI) and they are doing it with very limited external oversight. While policymakers struggle to keep pace - often more invested in winning the “AI race” than regulating it - the public voice remains largely absent from these crucial decisions.

This is where social movements come in. When people organise collectively, they give ordinary people collective power to demand a say in social progress - in the case of AI, in how and even whether certain technologies are developed. Movements can build momentum rapidly, adapt quickly to new developments, and mobilise large numbers of vocal supporters when conditions align.

Yet within the movement working to address AI risks, there are sharp disagreements about priorities. Some focus on AI harms affecting people today - from algorithmic bias to surveillance, killer robots to deep fakes. Others emphasise the existential risk to humanity if we continue on our current trajectory. Each side is critical of the other; for those focused on the potential extinction of humanity, short term harms are on a different order of magnitude and distract from real calamity; and for those focused on current harms being inflicted now, existential risk is overblown, hypothetical and a distraction from the real problems that are already here. Neither side currently has good information on what might motivate large numbers of the public to act.

This short report takes stock of where this burgeoning AI movement stands today. We map the emerging movement: what are the threats, how big and how soon might they come - if they are not here already? Who is working to address them, what’s missing, and how might civil society rise to meet this moment? Our focus is not on the technical details or projections about the capabilities of AI systems, but on the strategic civic response to them. Our aim is to help funders, campaigners, researchers, and policymakers see more clearly what exists, where the gaps are, and what types of people-powered action may be needed to keep humans and humanity at the heart of an emerging AI-dominated world.

Why Now

Three interconnected trends make this work more urgent than ever: the severe underinvestment in safety and public interest infrastructure, a lack of transparency and accountability from AI labs, and the rapid pace of AI development.

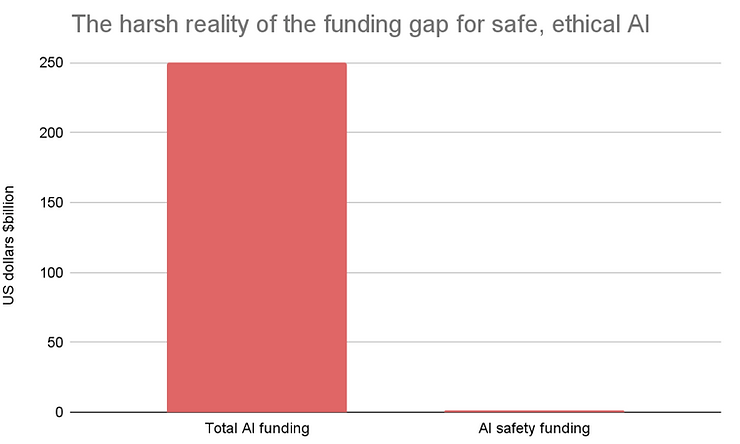

AI safety is hugely under-resourced, in talent and money: In 2024, over $250 billion was invested globally into AI development. Of that, less than 0.1% went to safety research; for example the US department for AI safety was given an initial budget of $10 million in 2024—and has now changed its name, so it no longer includes the word ‘safety’. Most funding comes from a small set of philanthropic actors, and even that funding is skewed toward technical alignment research and elite governance. While public interest in the risks of AI is growing—as seen in the popularity of major podcasts and media coverage—the infrastructure for activism, civic engagement, and democratic oversight remains strikingly thin and underfunded.

Figure 1. Total AI funding and AI safety funding in dollars, in 2024

This asymmetry constitutes a huge risk. As AI companies perceive themselves locked into a winner-takes-all AI arms race, ethics and safety are subordinate to speed. Without civic mobilisation, the default is private firms shaping a general-purpose technology with world-altering consequences, unchecked by the societies that will have to live - or die - with it. Let’s not forget that less than two years have passed since the CEOs of the major AI labs signed a statement saying,“Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war”. It is time they were held to account on this. As the Ada Lovelace Institute argue, public involvement is essential “so that technology can develop in alignment, rather than to an agenda driven by economically pressured policymakers and commercially driven technology companies”.

AI development lacks transparency and democratic accountability: The most powerful AI systems are being built behind closed doors by a handful of tech companies, with minimal public oversight or input. These labs are reshaping our collective future without meaningful consent or accountability. There are high levels of public concern about these systems—YouGov polling in early 2024 found that nearly two-thirds of the UK public are worried about AI’s impacts on jobs, democracy, and personal freedom—yet a report from the Ada Lovelace Institute and Alan Turning Institute reveals that people feel powerless to influence AI's direction. This democratic deficit means a potentially transformative technology is being developed without the knowledge or consent of those it will most affect.

Rapid accelerations in AI development: Breakthroughs in model capabilities are coming thick and fast. It’s not just the human-level performance reached on a widening range of tasks, but the speed with which those levels have been reached - and what that could look like soon if progress continues at the same, or a faster pace.

A study on AI supercomputers from April 2025 found that leading systems have doubled in compute performance every nine months, while hardware costs and power needs have doubled annually. Research by METR shows that the length of tasks AI models can autonomously complete is also doubling around every 7 months. And these systems are not confined to the lab. As AI systems become increasingly agentic, they are being quickly and extensively embedded - in workplaces, law enforcement systems, and national security operations.

A study on AI supercomputers from April 2025 found that leading systems have doubled in compute performance every nine months, while hardware costs and power needs have doubled annually. Research by METR shows that the length of tasks AI models can autonomously complete is also doubling around every 7 months. And these systems are not confined to the lab. As AI systems become increasingly agentic, they are being quickly and extensively embedded - in workplaces, law enforcement systems, and national security operations.

Figure 2: Speed of AI reaching human level performance on a range of tasks. Kiela et al. (2023) – with minor processing by Our World in Data. “Test scores of AI systems on various capabilities relative to human performance”

The Scope of this Work

This report is an early-stage mapping exercise. We are not attempting a comprehensive account of all AI harms or a complete directory of every relevant group. Rather, we aim to give an overview of:

-

The broad categories of risk posed by advanced AI systems—risks to whom, over what timescale, and with what likely magnitude.

-

The existing ecosystem of actors working to mitigate those risks—focusing primarily on grassroots movements and campaign groups.

-

The gaps that exist in terms of risk targets, strategies, geographies, and communities.

There are many different ways to categorise AI risks. Some frameworks focus on causes: malice, misalignment, misuse. Others focus on domains: discrimination, misinformation, loss of control, economic instability. Still others distinguish between near-term harms and long-term existential risks. In this report, we use a hybrid framework to clarify what’s at stake and who is working to address the threat.

Mapping the Threat Landscape

When people hear about AI risks, they often imagine something distant and abstract, often based on science fiction narratives—sentient machines (as in I, Robot), runaway algorithms (like The Matrix), or apocalypse (as in Terminator 2). But AI-related harms are already here, embedded in hiring software, recommendation engines, predictive policing, and viral disinformation. To shape an effective civic response, we need clarity on what these threats are, who they affect, and where they might lead.

This section offers a working map of key risk areas, structured by scale and time horizon.

A working taxonomy of AI risks

We group AI risks into three broad types, adapted from the UK’s 2025 International AI Safety Report and other public-facing taxonomies:

1. Malicious use

The use of AI to cause deliberate harm, including:

-

Deepfakes and disinformation

-

Cyberattacks, malware, phishing

-

Manipulation of elections or public discourse

-

Autonomous weapons, bioweapons, other weapons to cause mass harm

2. Malfunctions and misalignment

The risk of AI systems behaving in unintended or harmful ways, even without malicious intent:

-

Bias and discrimination in decision-making

-

Errors in life-critical domains (e.g. medicine, criminal justice)

-

Lack of transparency or explainability

-

Misaligned goals in powerful systems

3. Systemic risks

Large-scale social, economic, or environmental impacts:

-

Mass job displacement and labour market instability

-

Erosion of democratic norms and civic trust

-

Data theft, copyright infringement, threat to human creativity

-

Surveillance and loss of privacy

-

Resource extraction and environmental costs

-

Long-term existential risks from super-intelligent system

These categories are porous—one threat can lead to another. For instance, mass misinformation (malicious use) can undermine trust in elections and democracy (systemic risk). A highly capable AI system that fails to act as intended (misalignment) could have catastrophic consequences at scale (systemic risk).

Some examples of how risks are already showing themselves

1. Bias and discrimination

One of the most well-documented real-world harms from AI is algorithmic bias. For example, in 2020, Robert Williams, a Black man in Detroit, was wrongfully arrested—in front of his children—based on a faulty facial recognition match. He spent 30 hours in jail. He’d never been to the store where the alleged crime occurred. His story is not unique; the Algorithmic Justice League has documented multiple cases where facial recognition misidentified people of colour, leading to arrests, job loss, or reputational harm.

These are not bugs. They are systemic failures embedded in training data which disproportionately harm marginalised groups.

2. Misinformation and deepfakes

ChatGPT recently falsely claimed that a real Norwegian man, Arve Hjalmar Holmen, who has never committed a crime, had murdered two of his children. He has filed a defamation claim. Also in 2025, AI-generated images falsely depicting riots in downtown LA circulated on social media when President Trump sent in troops to respond to anti-ICE protests. The images were shared thousands of times, fuelling conspiracy theories and outrage, before being debunked. The previous year, deepfake videos began circulating of Taylor Swift fans endorsing Trump, part of a coordinated campaign to drive voter turnout under false pretences.

Of course, propaganda has long existed but AI changes the game, making it cheap, fast, convincing, and indefinitely scalable. As generative tools become easier to use, the challenge could move from detecting individual falsehoods to maintaining any shared sense of social reality.

3. Job displacement

While AI’s impact on jobs is still unfolding, early signals are clear. In 2024, a survey by the Trades Union Congress (TUC) found that 22% of UK workers had seen tasks automated by AI in the past year, often without consultation or protections. Many tech workers are already being replaced by AI and some companies like Duolingo have boasted about becoming ‘AI first’. Tech journalist Brian Merchant has documented countless personal stories of how people lost their jobs to AI. In June, research by Adzuna, the job search site found that the number of entry level jobs in the UK was down by a third since November 2022 (when ChatGPT was publicly released). Anthropic boss Dario Amodei recently said that AI could wipe out 50% of white collar jobs within five years.

The threat is economic, psychological and sociopolitical. As AI displaces work, it risks not only cutting off employment income, but also hiking unemployment rates and eroding people’s sense of purpose.

4. Loss of privacy and surveillance creep

AI-enabled surveillance is increasingly embedded in public life. Systems that track your face, voice, emotions, or typing patterns are now used in schools, workplaces, and public spaces, often without consent. In authoritarian regimes, such tools are already used to suppress dissent. Some Chinese citizens feel unsafe even outside of China, as they are surveilled online and at protests. According to a Wired investigation, the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has recently introduced facial recognition software into the phones of its officers. Even in democratic countries, surveillance capabilities are outpacing legal and institutional safeguards. Groups like Fight for the Future have campaigned—and had successes—against this creep, calling for bans on facial recognition in policing and public control over data.

5. Risks to humanity

At the far end of the risk spectrum lie scenarios that motivated much of the original AI safety field: the emergence of systems that are vastly more intelligent than humans and not aligned with our values. Although this sounds like science fiction, autonomous weapons systems (‘killer robots’) can already identify and kill individuals on the battlefield with very limited human oversight. Some argue that building systems with unprecedented intelligence and undefined applications is simply not possible to do safely.

The risks of superintelligent AI are currently harder to illustrate with individual stories but potentially of much greater magnitude. The UN’s 2024 resolution on AI governance explicitly cited the need to prevent “loss of human control” over powerful systems. Groups like the Center for AI Safety, Future of Life Institute, and Control AI argue that just as with pandemics or nuclear weapons, we must act before catastrophe; leaving it too late might, at its worst, mean the end of the human race. As Control AI argues, “Humanity’s default response to risks of this magnitude should be caution. Today, the position is to allow private companies to keep racing until there is a problem, which is as untenable as allowing private companies to build nuclear reactors until one melts down.”

While the probability of these outcomes is debated, their impact could be irreversible. And unlike other technologies, advanced AI could redesign itself, making course correction increasingly difficult with each new generation.

So the risks are clear, and they are legion. In the next section, we turn to the civic response. We look at the campaigners, educators, coalition builders, and movement mobilisers who are starting to take on the threats by putting the voice of the public at their heart.

How is Civil Society Currently Responding? Mapping the Movement

Although polling shows strong public majorities in favour of regulation, oversight, and pause measures, this has not yet translated into concerted, mass public action. Infrastructure for AI safety groups remains limited, and very few organisations are currently explicitly focused on helping people understand, track, and challenge AI deployment in their own lives and beyond. Most advocacy has been insider-focused: expert-driven, slow-moving, and disconnected from broader public energy. Now, a growing but scattered ecosystem of groups are beginning to challenge the direction of AI development—not from within labs or policy corridors, but through public voice, protest, and participation. This section maps some of the actors driving the beginnings of that shift.

We focus here on groups that place public engagement at their core: those informing, mobilising, representing, or giving voice to the people who are often left out of elite AI governance conversations. These are the early-stage architects of a people-powered AI safety movement. As with the risks, there are many ways to categorise these groups; academics at Bristol university group anti-AI responses as ‘Tame, Resist, Dismantle, Smash, Escape’. WeandAI suggests ‘Resist, Refuse, Reclaim, Reimagine’. There are many other taxonomies. Here, we group these organisations by their dominant strategy and how they seek to involve the public.

1. Protest, disruption and public mobilisation

These are groups applying civil resistance tactics to AI development—calling for pause, accountability, or bans on specific technologies.

-

PauseAI

A decentralised, international movement urging a halt to the development of frontier AI models until safety standards are in place. Known for their public demonstrations and clear, accessible communication on extinction risk. -

Stop AI

A civil resistance group demanding a ban on artificial general intelligence. Their direct action approach reflects growing urgency and frustration at the laggardly approach of governments to AI risks. -

People vs big tech

Innovative largely youth movement, campaigning against disinformation, social media hate, surveillance and demanding a better distributed tech ecosystem.

-

Control AI

UK based organisation ‘fighting to keep humanity in control’. 45,000+ people have signed their open statement on AI safety frontier models.

2. Narrative-shaping and watchdogs

These organisations expose current AI harms, challenge dominant narratives, and advocate for justice-focused AI.

-

Algorithmic Justice League (AJL)

Founded by Dr Joy Buolamwini, AJL blends research and storytelling to expose bias in AI, especially facial recognition. Their focus is on highlighting and mitigating biases in AI systems. -

Distributed AI Research Institute (DAIR)

Led by Dr Timnit Gebru, DAIR conducts interdisciplinary AI research rooted in ethics, focusing on the societal impact of AI. They challenge the industry through rigorous, community-rooted research. -

Fight for the Future

A veteran digital rights group using online organising, viral campaigns, and policy pressure to resist surveillance and defend civil liberties. Their AI-specific work is fairly new, but their infrastructure and reach could make them a key actor. -

AINow Institute

A research institute confronting the power of big tech power. Their goal is to ‘reclaim public agency over the future of AI’.

3. Public literacy and democratic engagement

These organisations focus on informing, equipping, and involving the public in decisions about AI, to help address AI’s ‘democracy problem’.

-

We and AI

A UK volunteer-led organisation focused on increasing public understanding and engagement with AI. They offer workshops, resources, and coalition-building rooted in values of equity and inclusion. -

Connected by Data

A UK group pushing for public involvement in AI and data governance. Their work reframes data and AI as democratic issues, not just technical ones. -

CivAI

A California-based nonprofit that uses interactive demos—build your own deepfake, write a phishing email—to give people visceral insight into AI’s risks. -

Citizens’ Assemblies on AI / Democracy Next

Facilitators of deliberative processes where members of the public discuss and shape AI policy recommendations. Their model offers an alternative to technocratic, big corporation decision-making. -

Global Citizens Assemblies

Of course AI is a global rather than a national problem and some organisations argue that we need the involvement of people at the same (global) level.

4. Infrastructure, field-building and political lobbying

Some organisations support civic engagement, helping build connective tissue for the movement and bring the public’s voice into legislation.

-

Ada Lovelace Institute

An independent research institute with a mission to ensure “data and AI work for people and society”. Play an important convening role within the AI community and do research to influence good AI policy. -

AI Incident Database

A searchable living archive of real-world AI harms. Like a “black box” recorder for AI failures, from deep fakes to election manipulation to surveillance—which helps activists, journalists, and researchers understand patterns of risk. -

Data & Society / Future of Life Institute / Humane Intelligence

While not grassroots groups, these organisations contribute critical research, convening, and communication that informs public-facing efforts to keep humans at the forefront of AI developments. -

Stop Killer Robots

A global coalition of over 250 NGOs campaigning for international law to prohibit autonomous weapons systems.

Observations and Propositions from the Map

-

The civic side is small, underfunded and loosely connected but could be amplified. Few groups operate at scale. Many are volunteer-run or single-issue focused. The ecosystem could benefit from regular events to bring all the constituent groups together to find their common overarching purpose. Funders supporting novel and innovative ways to engage and activate the public could have outsized impact.

-

Geographic skew. Most activity is concentrated in North America and Europe. Efforts to build public-facing AI safety infrastructure outside these regions remain scarce and under-supported.

-

There are gaps in movement infrastructure. Coordination, shared platforms, legal support, and cross-issue coalitions are all underdeveloped.

-

There is dissent. For example, those who are focused on harms already being experienced by people today and those whose focus is existential risk to humanity are often not well aligned. Note that this is not uncommon in social movements. In the climate movement, for example, tech solutionist and climate justice approaches are sometimes at odds. In a movement, groups needn’t all collaborate or cooperate, but it is usually helpful to understand where other groups are coming from and for actors to understand their role in the broader movement ecology.

-

Narrative power is a key battleground. The idea that “AI development is inevitable” is dominant—not surprising given the power of the tech giants. Several groups aim to challenge that, though it is currently not clear what messaging is most effective. Studies investigating which strategies are most effective would be helpful in this context.

-

The AI movement can learn from other movements. Creating a movement that is more than the sum of its parts, out of several atomised organisations requires a lot of work on the interstices. Organisations like NEON who help with communications, operations and movement building, and the AYNI institute who provide training for activists and organisers are a key part of these ecosystems for other movements.

-

A fund committed to ethical AI could make a real difference. The fund could support groups working outside of traditional structures (corporations, unions), by being set up to support informal and un-constituted groups with innovative approaches as well as established groups (like the Climate Emergency Fund).

Conclusion

There are many, highly varied risks emerging from current AI developments. Without a strong civic response, these risks present serious societal challenges. Given the nature of AI developments (fast, unpredictable, wide-ranging), social movements may be particularly well-suited to respond. They could be critical for putting the necessary pressure on tech companies and policy makers to proceed with the caution the public wants; movements could demand serious and multiple existing and emerging concerns to be properly addressed.

The AI movement is aware of current threats, and is starting to mobilise against risks likely to materialise soon and in the longer term (including extinction-level threats). We hope that this report encourages more efforts in this space, giving advocates an overview of current projects and initiatives, pointing other researchers to knowledge gaps where findings could help give actionable insights to movement actors, and encouraging funders to urgently support promising approaches. [1]

[1] The introduction and ‘why now’ sections of this report were amended on 1st September to better reflect the balance of views between those with more immediate AI concerns and those more focused on longer term harms.

About Social Change Lab

Social Change Lab conducts empirical research on social movements to understand their role in social change. Through research reports, workshops, and trainings, we provide actionable insights to help movements and funders be more effective. You can find all of our research projects and resources on our Research page. You can contact us at info@socialchangelab.org