What Makes a Protest Movement Successful?

Summary

Social Change Lab’s previous work on protest outcomes found that Social Movement Organisations (SMOs) that use protest as a main tactic can significantly impact public opinion, voting behaviour, public discourse and to a lesser degree, policy outcomes. Despite this, it’s not clear what strategies and tactics these movements should pursue in order to maximise their impact on these outcomes.

As a result, we conducted a 6 month-long research project looking into the factors which make some protest movements more successful than others, focusing primarily on Western democracies, such as those in North America and Western Europe. In this report, we provide a synthesis of the research that we conducted using a variety of research methods. These methods include a literature review, public opinion polling, expert interviews, policymaker interviews, and a case study. This report specifically focuses on protest-based movements, movements that use protest as a key tactic, as opposed to social movements more broadly. For example, this report is more aimed at how the climate movement or animal advocacy movement could improve, rather than an intellectual social movement such as effective altruism. That said, we believe some factors will overlap for both protest-focused movements and non-protest focused social movements.

We believe this report could be useful for grantmakers and advocates who want to pursue the most effective ways to bring about change for a given issue, particularly those working on climate change and animal welfare. We specifically highlight these two causes, as we believe they are currently well-suited to grassroots social movement efforts.

The report is structured so we only present the key evidence from our various research methods for the success factors we believe are the most important, such as numbers, nonviolence and diversity. Full reports for each research method are also linked throughout for readers to gain additional insight.

Contents

1. Summary

1.1 Summary Table

1.2 Illustrative Findings

1.3 Scope of this report

2. Introduction

2.1 Why we think this work is valuable

2. 2 Research Questions & Objectives

2.3 Audience

3. Methodology

4. Violence

4.1 Literature Review

4.2 Expert interviews

4.3 Policymaker interviews

4.4 SHAC Case Study

5. Numbers (size of protest or protest movement)

5.1 Literature Review

5.2 Expert interviews

5.3 Policymaker interviews

6. External Factors

6.1 Elite Allies

6.2 Public Opinion

6.3 Luck

7. Diversity

7.1 Literature Review

7.2 Expert interviews

7.3 Policymaker interviews

8. Other potentially important factors

8.1 Commitment and Unity

8.2 Radical Flank Effect & Disruption

8.3 Trigger Events and Protest Timing

8.4 Intra-organisational factors (e.g. governance, systems and team experience)

8.5 Protest frequency and protest length

9. Future work that could be promising

10. Limitations

11. Conclusion

Summary Table

Below, we scored success factors on two different scales, one to highlight the causal importance of the success factors to achieving desired outcomes, and another to highlight the strength of evidence behind our claim. Our magnitudes of expected effects are given relative to other factors. However, there are often many different outcomes that movements or specific social movement organisations (SMOs) are optimising for, such as changing public opinion, policy, public discourse, and so on. We present our expected effect sizes assuming that one could translate them all into a unified metric of success.

The ‘strength of evidence base’ column also expresses the relative strengths of the evidence bases. For example, ‘Strong’ indicates high levels of agreement between all relevant academic studies on this topic, as well as supporting evidence from expert interviews and other research methods. ‘Weak’ might reflect substantial disagreement in the academic literature, there being few empirical studies on this topic or that the evidence was derived solely through expert interviews. The evidence related to each outcome, and our estimations regarding its importance are explained further in the sections below.

Table 1: Our current estimates, and evidence bases behind these estimates, for the relative causal importance of different success factors.

Illustrative findings

Below are some of our notable findings, that highlight some of the summary claims in the table above:

-

Teeselink and Melios (2021), when analysing the impact of Black Lives Matter protests in 2020 on voting behaviour, estimate that a percentage point increase in the fraction of the population that goes out to protest (i.e. larger protest size) raises the share of Democratic votes by 5.6 percentage points.

-

Wasow (2020) finds that during the US Civil Rights Movement, non-violent protest was more successful in increasing Democratic vote share than was violent protest, which had negative consequences. He found that nonviolent protest resulted in a 1.6 percentage point higher Democratic vote share relative to a ‘control’ county with no protest, whereas violent protests increased votes for Republicans by 2.2 - 5.4 percentage points (in opposition to the aims of the Civil Rights movement).

-

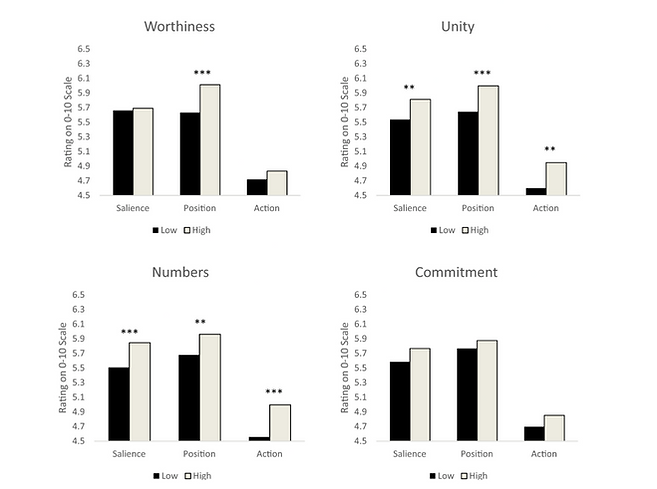

Wouters (2019), using an experimental approach, finds that the diversity of a protest is one of three factors that influence the public to increase support for an issue. Worthiness (or nonviolence) and unity also led to increases in public support for a cause after being exposed to protests, whereas changes in commitment of the protestors or size of protest did not.

-

Simpson et al. (2022) uses an experiment to find that radical tactics, and not radical goals, can increase support for more moderate groups. This study, examining the climate and animal advocacy movements, shows that radical tactics can boost support for more moderate groups without harming overall support for a movement’s policy goals.

1.3 How to read this report

In this report, we summarise the key findings from various research methods (e.g. our literature review), rather than replicating them in full. For example, in the violence section, we reference the papers with the most valuable and relevant evidence from our literature review, rather than all the papers that examine violence as a strategy. For those who want to read more into a particular success factor or methodology, we encourage you to read the full, linked reports. All sections are intended to be standalone, which means that some papers, which support multiple factors, are repeated in several sections.

1.4 Scope of this report

Rather than this report being an exhaustive handbook of what protest-focused movements should do to be successful, it is a summary of the current available evidence. Due to some factors being easier to measure relative to others, such as the importance of protest size relative to internal culture, we believe there is a bias in this report for factors that are more measurable.

Additionally, as identified in our protest outcomes report, there are often many different outcomes that movements or specific social movement organisations (SMOs) are optimising for, such as changing public opinion, policy, public discourse, or more. Due to this, it can be hard to compare some factors to one another, as they might be trying to optimise for different outcomes. Throughout the report, we note where specific factors might be more successful in achieving some outcomes relative to others.

This report covers high-level movement strategy, such as decisions around how much relative effort movement leaders should put into size, diversity, and internal governance. We don’t cover more on-the-ground details on how to run effective campaigns, as we think this has been covered fairly well in other pieces of work. For this, we refer those interested in the nuts and bolts of how to campaign effectively to the following resources: Activist Handbook, The Commons, Campaign Bootcamp and Effective Activist to name just a few.

Additional limitations can be seen in our Limitations section.

Introduction

2.1 Why we think this work is valuable

In our report on protest outcomes, we found that Social Movement Organisations (SMOs) that use protest as a main tactic can significantly impact public opinion, voting behaviour, public discourse and to a lesser degree, policy outcomes. We think that if our findings on protest outcomes are accurate – that protests can significantly alter public opinion and/or affect policymaker’s beliefs – then there is a strong case that philanthropists and social change advocates should be considering this type of advocacy alongside other methods.

Additionally, we believe this is an especially neglected area of research, given that protests are an extremely commonly used tactic for achieving social change. For instance, we believe that we are the first to conduct a (preliminary and uncertain) cost-effectiveness analysis of a social movement organisation, and the second to commission bespoke public opinion polling to understand the impact of protest on public opinion. We see this as an opportunity to add value by providing research that addresses some unanswered questions about the role of social movements in improving the world.

2.2 Research Questions & Objectives

Primary research questions we have been investigating for this report:

-

Which tactics, strategies and factors of protest movements (e.g. size, frequency, diversity, etc.) most affect their chances of success of achieving their desired outcomes? Such as changing public opinion, influencing policymakers, shifting public discourse, and so on.

-

How important are factors within a movement or organisation’s control, such as their strategy or structure, relative to external societal conditions, such as pre-existing public opinion or friendly elites?

Other questions we are tackling or will tackle in the near future can be seen in our section on future promising work.

2.3 Audience

We think this work is valuable to two audiences in particular:

-

Philanthropists seeking to fund the most effective SMOs - For example, if we discover that SMOs are generally more successful if they incorporate good governance and strict nonviolence, then grantmakers should fund these organisations (all else being equal) relative to SMOs who don’t.

-

Existing social movements - who can employ and integrate best practices from social science literature to make their campaigns more effective. This includes Effective Altruist community-builders, who thus far seem to have made relatively little effort to learn from previous social movements and examine why and how they succeeded or failed.

Methodology

As a preliminary step, we sought to understand the academic literature pertaining to protest movement success factors. We conducted a comprehensive literature review to identify key papers and analyse their robustness. Our literature review found several success factors that were validated by multiple compelling academic studies. However, the overall evidence base within the academic literature was relatively small, and we had to rely on other methodologies to supplement our conclusions. For instance, we only found three relevant studies that examined the importance of diversity and unity, compared with 11 seemingly robust studies on the question of whether nonviolence or violence is generally a more effective strategy.

We decided to tackle subsequent research by approaching our research questions from many different angles and using several different methods. We believe this is a more robust way of tackling our research questions, as no single methodology provides an empirically foolproof approach, given the limited evidence base. Instead, we attempted to evaluate the evidence base for social movement success factors using a variety of different methods, to understand where this broad evidence base converges or diverges. We explain the methodologies in-depth in Appendix A and in the full reports, but in summary, the research methods we used are shown in the table below. The limitations of our overall methodology are addressed in more detail in the Limitations section, with specific research-method focused limitations in our individual reports.

Throughout this report, we focus on social movements that use protest as a main tactic within their activities. We define protest fairly broadly, using the classification provided by Beer (2021), which finds 346 different methods of civil resistance.

Table 2: This table highlights the various methodologies used to produce the findings in this report.

4. Violence

Whether violent protests are more or less likely to succeed than nonviolent protests is a hotly debated topic among those who study social movements and protest activity. The question is an important one - it is useful to know whether there is some downside to activists who only carry out nonviolent activities. The evidence suggests that nonviolent protests are more likely to be successful than violent protests.

To clarify, we are referring only to protests that are clearly violent, such as attacks against individuals, protests where people are threatened with physical harm, rioting, etc. Additionally, most of the literature we examine treats property destruction or damage to objects as violent, so this is reflected in our work (even though this is a contentious distinction). We are not referring to protests that are disruptive but nonviolent, although the literature occasionally conflates violent protest with disruptive protest. We think evidence against violent protest should not necessarily be taken as evidence against nonviolent yet disruptive protest.

Most of the available literature suggests that violence reduces the chance that a protest movement will succeed, and our conversations with academics generally corroborate this view. That being said, we are not claiming that this is a settled debate, nor that all of the literature is consistent on this, but we are claiming that the majority of high-quality studies indicate that nonviolent protests are more likely to be successful than violent protests. We should add that the question of what is considered violent vs nonviolent is a highly ethical one, and there is widespread disagreement on the topic. As a result, both researchers and advocates may have biases that influence both research on this topic, as well as how to apply research on this topic to social movement activities.

4.1 Literature Review

In our Literature Review on factors that make protests more likely to succeed, we found that the consensus in the literature was generally that nonviolent protests are more likely to succeed than violent protests. Studies that showed that nonviolent tactics are more likely to lead to positive outcomes were:

-

Wasow (2020) demonstrates with an instrumental variable approach that during the US Civil Rights Movement, non-violent protest was more successful in increasing Democratic vote share than violent protest. He found that nonviolent protest resulted in a 1.6 percentage point higher Democratic vote share relative to a ‘control’ county, whereas violent protests increased votes for Republicans by 2.2 - 5.4 percentage points (in opposition to the aims of the Civil Rights movement).

-

Research from Feinberg et al (2017) also showed that extreme activism (which was usually violent action), resulted in reduced public support for the issue being protested and fewer people identifying with the protest movement.

-

Work by Muñoz and Anduiza (2019) supports the hypothesis that nonviolent protests are better at building public support for a social movement. They examine the 15-M anti-austerity protesters in Barcelona, exploiting a sudden shift from nonviolent activity to violent riots and protests in 2016. Surveys were conducted both before and after the sudden shift from nonviolent to violent activity. The level of support for 15-M decreased by 12 percentage points after the shift, from 65% support to 53% support. It should be noted that the fall in support was concentrated among voters of parties that did not have sympathy for the movement to begin with, whereas the fall in support among ‘core supporters’ was smaller. The figure below shows the interaction effect between an individual’s past vote and change in support for the movement.

Figure 1: The interaction effect between past vote and change in support for the protest movement, after the public being exposed to riots. Source: Muñoz and Anduiza (2019)

-

Wouters and Walgrave (2017) conducted an experiment which exposed Belgian legislators to different news stories showing protest activity, manipulating whether the stories depicted protesters as ‘worthy’ (serene atmosphere, calm and peaceful demonstrators, etc.) or ‘unworthy’ (disruption initiated by protesters, broken shop windows shown, etc.). They found that legislators shown ‘worthy’ protesters were more likely to take the position of the protesters, although they were no more likely to say:

-

that they would actually take action in support of the protesters or

-

that they found the issue they were highlighting to be particularly salient (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 2: Predicted Values of Salience, Position, and Intended Action Effects by Worthiness, measured in Belgian legislators. Source: Wouters and Walgrave (2017).

Whereas the following studies showed that violent tactics can have positive outcomes, at least in some cases:

-

Shuman et al. (2022) analysed the impact of violence during the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, using three groups: people living in areas with no violent protest, people in areas with only nonviolent protests, and people living in areas with both. They found that protests involving both violent and nonviolent activity were the most likely to be successful in persuading conservatives in relatively liberal areas (a group who is relatively resistant to BLM’s policy goals).

Figure 3: Support for the policy goals of Black Lives Matters, by political ideology and the combination of violent and nonviolent protests in a particular area. Source: Shuman et al. (2022)

-

Enos, Kaufman and Sands (2019) find that the violent riots that took place in 1992 in Los Angeles in response to the beating of Rodney King resulted in changes in voting behaviour in referendums that took place in 1992. They examined two referendums that occurred after the riots - one relating to public schools, an issue considered by many to be linked to African American prospects, and one relating to universities, considered not to be. They use a difference-in-differences design comparing the change in support for funding public schools to the change in support for funding higher education, finding that the support for funding public schools increased more than the support for funding higher education in the Los Angeles Basin. This was not true of other parts of California, suggesting that the violent riots may have had a causal and positive impact on voting behaviour in Los Angeles.

Despite the observation that violent tactics are associated with a movement's success in certain contexts, the overall evidence suggests that non-violent tactics are more effective in increasing public support for an issue, persuading policymakers and positively influencing voting behaviour.

4.2 Expert interviews

In our conversations with social movement experts and academics who study the impacts of social movements and protest, we asked a range of questions to understand the extent to which violent protests were more or less likely to succeed than nonviolent protests. Generally, there seemed to be a common view that most of the literature points to the fact that violent protest is generally less likely to be successful than nonviolent protest, but that there may be specific circumstances in which violent protest can also be more successful than nonviolent protest, dependent on the political context in which the protest activity is occurring.

Illustrative Quotes:

-

“There are lots of similarities across nations about the ineffectiveness of violent protest, this is true whether you’re in an autocratic or democratic context, except in the US where it might be more socially acceptable.”

-

“We can say with a reasonable amount of confidence that violence is probably less effective than nonviolence, and violence against the police is a terrible idea.”

-

“A question like ‘Do extreme protests work?’ might be difficult to answer because it will be dependent on context. There’s also the case that even a violent or extreme protest might lead to protesters developing more of a commitment to the cause - movements are kept alive by people who are passionate.”

-

“Lots of advocates of violent protest argue for the ‘radical flank effect’, but it seems really obvious that sometimes the radical flank effect will work and other times it won’t, you can’t just cite the radical flank effect as a justification for violent protests.”

4.3 Policymaker interviews

During our interviews with three civil servants, the topic of the efficacy of violent/nonviolent protest was generally less likely to come up, as civil servants have predominantly been exposed to disruptive but nonviolent protest. That being said, there are a few quotes that are relevant to the debate, although not enough that a reader should update significantly on the basis of these conversations. For the most part, civil servants took it as given that nonviolent protests were more likely to influence legislators than were violent protests.

Illustrative quotes:

-

“Non-violent disruptive protest is likely to get the most attention, but whether the attention is positive or negative is contingent on the circumstances.”

-

“Non-violent direct action seems to attract the most attention. This can go both ways - it can cause a lot of inconvenience and shut things down and make people annoyed, or it can make people pay attention to whatever issue is being protested about.“

4.4 SHAC Case Study

We carried out a case study examining the impact of Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty (SHAC), an international animal rights campaign that aimed to shut down Huntingdon Life Sciences (HLS), a Contract-Research Organisation accused of animal rights violations. SHAC ultimately failed in their goal, and so lessons can be learnt about why exactly SHAC were unable to shut down HLS.

We emphasise that it is difficult to make causal inferences from a single case study, and accordingly we urge readers not to assume that what worked for SHAC would work for other activists, or that what didn’t work for SHAC would not work for other activists. Some things highlighted in the case study that are relevant to how violence impacts the chance of success include:

-

Violent actions by activists campaigning against HLS received disproportionate amounts of media coverage, and that media coverage was overwhelmingly negative. Negative media in of itself does not mean the overall consequences were negative, but based on Feinberg, Willer & Kovacheff (2020), we assume that negative media coverage of violence is more likely to lead to reduced identification with and lower support for the aims of the animal advocacy movement.

-

One attack against an HLS employee (the attack on Brian Cass), likely led to a greater amount of negative attention from the British government. An Early Day Motion was tabled in the House of Commons explicitly condemning the attack, and received 55 signatures from Members of Parliament. This attack potentially resulted in more severe government repression, such as the passage of the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act, which was likely done in response to SHAC activities.

-

In response to SHAC’s actions relating to a planned loan to HLS, Tony Blair claimed that he was ‘on the side of science’, and a Downing Street spokesman referred to the ‘intimidation, thuggery and violence’ of animal activists.

-

That being said, the negative media attention as a result of violent activity may have also had some benefits: the portrayal of SHAC as violent and liable to commit extreme actions against companies may have led to some companies deciding to cease cooperation with HLS.

-

The nonviolent activism by SHAC received significantly less media attention than the violent activity committed by activists against HLS. While we believe that SHAC was harmed overall by being portrayed as violent, it remains notable that their nonviolent activity received far less attention and if activity against HLS had been exclusively peaceful, it is unclear how much impact SHAC would have had.

5. Numbers (size of protest or protest movement)

Our overall assessment is that numbers is likely to be one of the most important factors in determining success. In our literature review, expert interviews and policymakers interviews, our findings consistently showed that the size of a protest or protest movement had a significant impact on protest outcomes. There is some evidence to the contrary in our literature review, but we generally believe the evidence supporting numbers is much stronger. Overall, we are reasonably confident that this is one of the three most important factors in determining protest or protest movement success.

5.1 Literature Review

In our literature review on success factors, we find several studies that examine the impact of protest size on efficacy, using a range of experimental, quasi-experimental and observational methods. Experimental work by Wouters and Walgrave (2017) looked at the impact of various success factors on policymakers and they found that protest size had the strongest impact on policymakers. Not only did protest size influence the perceived salience of the issue, but it also increased the likelihood of policymakers taking a stance similar to the protestors and taking action on the issue (e.g. proposing legislation or asking a question in Parliament). This is one of the few pieces of compelling experimental results quantitatively comparing success factors, meaning we put strong weight on this study.

Interestingly, subsequent experimental work by Wouters (2019) tests the same WUNC factors, as well as diversity, but this time the sample is drawn from the public, rather than policymakers. In this case, Wouters finds that the size of the protest has no relationship with public support for the cause. This highlights a notable difference: while the size of the protest is particularly compelling for policymakers, it seemingly does not matter for the public.

One example of quasi-experimental work on this question comes from Teeselink and Melios (2021), who use an instrumental variable technique to estimate the impact of Black Lives Matter protests in 2020 on voting behaviour. They found that in areas with low rainfall (and therefore high protest turnout), there was on average a greater proportion of votes for Democrats relative to areas with high rainfall (and small protest size). Specifically, they estimate that each additional percentage point of the population who go out to protest raises the share of Democratic votes by 5.6 percentage points. Other evidence in our Protest Outcomes Literature review also shows that the number of people at a protest matters. For example, Madestam et al. (2013) also use Instrumental Variables to estimate the impact of Tea Party protests on Republican vote share; they find that low rainfall is associated with larger protests, which in turn causes an increase in the Republican vote share. They estimate that a 0.1 percentage point increase in the percentage of the population protesting corresponds to a 1.9 percentage point increase in the share of Republican votes.

Walgrave and Vliegenthart (2012) examine protests between 1993 and 2000 in Belgium, looking at the impact of (mostly) nonviolent and legal protests on questions in parliament, decisions by government, and passed legislation. They found a significant impact of protest size on legislation - the larger the number of protesters, the more likely it is that legislation is affected. On the other hand, protest size did not have a significant effect on decisions by the government or on speeches/questions in parliament. Walgrave and Vliegenthart used a large data-set of 3,839 demonstrations, 1,198 pieces of legislation and 180,265 news items, across 25 issues, which we believe makes this piece of evidence fairly strong.

Figure 5: Identified causal relationships between protest size, media and legislation, from over 25 issues in Belgium from 1993 to 2000v. Source: Walgrave and Vliegenthart (2012)

Other studies point to negligible, or even negative, impact of protest size on outcomes. King and Soule (2007) fail to find any impact of protest size on chance of success, when considering the impact of protests on the stock price of US corporations between 1962 and 1990. The authors claim that protests can decrease stock prices by reducing investor confidence, for example, by amplifying existing shareholders' concerns and drawing attention to specific organisational issues. Additionally, they can impose direct costs on a business, potentially through boycotts or a blockade, which may affect future cash flow. Despite this, they note that there is no significant correlation between the size of the protest and the change in stock price, although they do find a significant negative correlation between the length of the protests and stock price.

Butcher and Pinckney (2022) find that in Muslim countries, an increase in protest size negatively impacts the chance of concession from the government. Moving from the median number of protesters (1270) to the 90th percentile number of protesters decreases the chance of government concessions by 17 percentage points, on average. This finding may not be generalisable to a Western context, but remains an interesting result. The proposed mechanism is that governments anticipate that Fridays will have more people at protests, and thus the increased number is no surprise to the government - as governments seem to be more responsive to unanticipated protests. This point about unexpected groups, or unanticipated numbers, being particularly persuasive to policymakers or the government is corroborated by our expert interviews. Overall, we think this evidence is somewhat interesting, but the decrease in the chance of concession seems implausibly large, so we think it’s possible that the researchers didn't exclude all the necessary confounders for their design (using protest day as Friday as an exogenous variable).

5.2 Expert interviews

The most common view amongst the 4 academics and 6 social movement experts that we interviewed was that numbers, or protest movement size, is a key determinant of success. As above, it was pointed out that numbers might matter much more to politicians, who can use protest size as a gauge of public opinion, relative to the public. Similarly, two academics pointed out that an extremely important factor for protests or protest movements is an unexpected presence, which could manifest via a much larger than expected turnout, or a group that is unlikely to protest often. One academic also noted that there is very little academic research into the impact of small protests, which are the norm overall (i.e. very large protests are rare).

Illustrative quotes:

-

“The public has a different logic to legislators. Politicians are thinking about public support so the ‘numbers’ element might make more of a difference to them. “

-

“Although politicians invest so much effort in discovering public opinion, often they don’t have good models, so they might use protest and the numbers at a protest to get a sense of public opinion.”

-

“The number of people at a protest is probably the most important factor in its success, but this is somewhat obvious to protestors.”

-

“It’s worth noting that it’s very unclear what effect small protests are likely to have - some studies looking at small protests against austerity in Greece, Spain, and Portugal seem to find that they had pretty much zero effect. Very small protests seem really different to large protests, and the evidence they are effective is much less strong.”

-

“It’s also worth noting that, in discussions with Belgian legislators, there was a common view that what really led to protest success was there being an unexpected presence - if the numbers were dramatically higher than legislators had expected, if there were certain types of protesters there who differed from those you would usually expect to be in attendance, etc.”

5.3 Policymaker interviews

The three UK Civil Servants we interviewed all agreed that a larger protest movement or individual protest was a much more compelling signal to policymakers relative to a small protest. This was, by a large margin, the factor most mentioned in our interviews and the one our respondents believed was the most important success factor of social movement organisations in terms of influencing policy. The main reason is larger numbers signal higher levels of public support, something policymakers should consider in their decision-making.

Illustrative quotes:

-

“Movements that attract large numbers (e.g. thousands or tens of thousands) are much more likely to be acknowledged as public opinion signals relative to small protests.”

-

“Larger and more frequent protests provide much more compelling public opinion signals relative to small protests.”

-

“Bigger movements generally seem to be more persuasive and compelling”

6. External Factors

In this section, we outline the evidence around external factors, factors outside of the direct control of an SMO, such as public opinion when a campaign launches, the presence of elite allies in government, or luck. We should note that we haven’t paid as much attention to external factors as we have to internal factors. Because social movement organisations mostly cannot impact external factors (with some exceptions - such as gaining elite allies), we have focused mainly on internal factors. However, there is some evidence that elite allies, public opinion, luck, and unrelated media coverage may also contribute to protest movement success.

6.1 Elite Allies

6.1.1 Literature Review

The extent to which the presence of elite allies has an impact on the chance of protest success is disputed. A more detailed summary of the literature can be found in our literature review, but we summarise several of the most important papers below:

-

In their 2010 literature review, Amenta et al. (2010) note that influencing legislators can be beneficial for social movements, through the introduction of bills aligned with the objectives of social movements and help getting relevant bills through the legislature. This claim is largely based on Amenta et al. (2005), which identifies legislators as a key actor in the US pension movement.

-

Giugni (2007) similarly highlights the impact of elite allies, claiming that social movement success requires both public opinion to be sympathetic to the positions of the protesters and for the protesters to have political allies. He calls this the ‘joint-effects model’, using data from ecology, anti-nuclear, and peace movements in the United States. He found that there was a highly significant interaction effect between protest, public opinion, and political allies on spending for both environmental protection and reducing spending on nuclear energy, but no similar effect for the peace movement.

-

On the other hand, Olzak et al. (2013) find that members of Congress who are allied with activists are less successful in passing legislation than members who are not allied with protest movements. This does not necessarily indicate that protest movements lose out from having political allies, but it may be that legislators sympathetic to protest movements have less influence if their formal association is known. The reason, according to the authors, is that Members of Congress who are more allied with movement organisations are more likely to hold extreme views. Therefore, these Members of Congress have to compromise more in often delicate political negotiations, leading to the observed higher rates of failure.

6.1.2 Expert Interviews

There was no consensus among experts interviewed on the role of elite allies. That being said, there was some discussion about the importance of elite allies that is worth highlighting:

-

“Elite allies seem to be immensely important, because legislators are ultimately the people who drive the changes. The reception that protest receives from elites may account for 80% of the variance in outcomes.”

-

“Sunrise Movement got a lot of media attention when AOC decided to join their takeover of Nancy Pelosi’s office.”

-

“There is disagreement over the role of public opinion, the role of elite allies, and the role of party support, as it all depends so much on the context.”

-

“There may also be other routes to legislative change that involve increasing the chance of having elite allies by changing public opinion - for instance, if a protest movement increases the salience of climate change, this may result in, for left-wing movements, for instance, more Green Party legislators, who may act as elite allies to climate protesters.”

6.2 Public Opinion

6.2.1 Literature Review

The extent to which a social movement has public opinion on its side may impact its likelihood to succeed. Giugni’s research on the joint-effect model claims that protests require both elite allies and supportive public opinion in order to be successful. There is limited and mixed evidence on the importance of public opinion including:

-

Agnone (2007) posits an ‘amplification model’, where there is an interaction effect between public opinion and protest to influence legislators. Looking at time-series data in the US between 1960 and 1998, he finds that there is an amplification mechanism between environmental protest and public opinion: Protest amplifies the impact of public opinion on legislator behaviour by raising the salience of an issue.

-

Bernardi et al. (2020) find a similar amplification effect between protest and public opinion relating to specific issues such as housing, unemployment, and education - but for most issues no evidence of an amplification effect is found. Legislators seem to be more responsive to protests on ‘bread and butter issues’ that strongly impact citizens’ lives and may become an issue in upcoming elections if not addressed. They argue that the impact of protest is highly contingent, noting that ‘Only if protesters’ signal is strong and supported by public priorities will protest matter for attention changes’.

-

Burstein (2020) reviews studies into whether advocacy is more likely to be effective at changing legislator behaviour on ‘high-activity issues’ or ‘low-activity issues’, meaning issues that are particularly controversial or have received a significant amount of attention from advocacy groups in the past (for instance, abortion is classified as a high-activity issue whereas monetary policy is considered a low-activity issue). He finds that whether the issue is high- or low-activity is not significantly correlated with its chance of success.

6.2.2 Expert Interviews

Some experts believed that social movement organisations using protests were more likely to be effective if they had public opinion on their side. One useful claim was that legislators are particularly impressed by protests that don’t only consist of the ‘usual suspects’. That is, protests that included groups of people they wouldn’t normally expect to see at protests were seen as more reflective of public opinion than protests with ‘typical’ protesters. Another useful claim was that protests with public opinion on their side are able to get away with more disruptive protests.

Illustrative Quotes:

-

“Change happens because of legislators - even if a protest can change public opinion, change will not happen unless legislators are convinced that public opinion has changed. The signals of public opinion that politicians rely on are not necessarily signals that actually show what public opinion is.”

-

“A very strong protest movement that has public opinion on their side is likely to get away with disruptive protest, and can inflict costs on legislators that may make them more likely to be successful.”

-

“Politicians are becoming much more dependent on public opinion because most of the public are floating voters.”

-

“The personal ideology of legislators is an important factor in policy making. This and public opinion are the two main drivers of policy making.”

-

“If you look at the drivers of policy-change, there is a large consensus that general public opinion is very important in impacting legislation.”

-

“Although politicians invest so much effort in discovering public opinion, often they don’t have good models, so they might use protest and the numbers at a protest to get a sense of public opinion.”

Whilst these claims agree that public opinion is important in impacting the behaviour of legislators, we note that this is not the same as claiming that public opinion interacts with protest activity to impact legislators (as per the aforementioned amplification effect).

6.3 Luck

6.3.1 Expert Interviews

The experts we spoke to were clear that luck has a very significant role to play in social movement success. Because legislator behaviour and public opinion are contingent on so many different things (many of which cannot be predicted in advance), it becomes inevitable that noise and luck can impact the chance of success. A common theme among experts we spoke to was that social movement success is incredibly difficult to predict, indicating that luck might be a significant factor.

Illustrative Quotes:

-

“It can be extremely difficult to figure out why a movement did or did not

succeed - there are so many moving parts and variables. An analysis that says ‘Movement X failed only because of Y’ is guaranteed to be simplistic.” -

“One thing worth mentioning is that the right conditions need to exist for a mass protest movement to emerge. While we might not be good at predicting this, we know when it’s easier to frontload: when you have a pre-existing base, when you have trigger events, when you have experienced leadership.”

-

“You also can’t downplay the impact of luck in social movement success”

-

“The odds are people will always lose when trying to win for your community. However, you can take advantage when the moment is right. The world is unpredictable, and these opportunities do arise, so it’s important to know how to win power when the external conditions are suitable.”

6.3.2 Public Opinion Surveys

Social Change Lab conducted a survey before and after a wave of protests by Animal Rebellion to see if attitudes towards climate change and animal agriculture changed from before the protests occurred to after they took place. Our surveys found that there was no significant change in attitudes throughout the 2-week campaign and that relatively few people had heard of Animal Rebellion after the protests took place. This is almost certainly due to headlines being dominated by the replacement of the Prime Minister and the death of Queen Elizabeth, neither of which were predictable when the protests were organised.

In the second survey, 64% of respondents said that they knew ‘nothing at all’ about Animal Rebellion, a similar proportion to those saying they knew ‘nothing at all’ about the Stop Animal Cruelty Coalition, a group that does not exist. This indicates that very few people heard about the protests, and they likely had little impact on public opinion or legislator behaviour, largely due to factors outside of Animal Rebellion’s control.

We also conducted polls before and after protests by Just Stop Oil. In this case, there were no large news events competing for media coverage. The survey results below show that many more people had heard of Just Stop Oil after the protests than in the Animal Rebellion case. It is also worth noting that Just Stop Oil likely received more absolute news, due to organising larger and potentially more disruptive protests.

Figure 6: Awareness of both Just Stop Oil and Animal Rebellion after their protests occurred. Source: Public Opinion Polling for Animal Rebellion’s campaign.

7. Diversity

In this context, diversity refers to the composition of the protest or protest movement; it can mean standard demographic variables (e.g. age, class, gender, ethnicity) and also more specific societal groups (e.g. doctors, school children, employers, employees, etc.). Across our literature review, expert interviews and policymakers interviews, we find that greater diversity is likely to increase the chances of protest or protest movement success. Specifically, greater diversity is likely to appeal to the public, increasing the odds that they will identify with the movement, and therefore participate. Diversity also makes an issue more compelling to policymakers, as it demonstrates that a wide range of the public cares about an issue, rather than a narrow self-interested bloc. We think it’s amongst the top 5 most important factors for success in this report, but the evidence on this is fairly limited, so we’re relatively unsure.

7.1 Literature Review

In our literature review on success factors, we find relatively little evidence on the impact of diversity on success. Wouters and Walgrave (2017) manipulated the degree of diversity in the vignettes of protests shown to legislators - some legislators were shown images of an asylum protest that included only Afghan and African protesters, whereas others were shown protests that also included white participants. There was no significant effect of diversity on the legislators, and the results were ultimately not included in the study due to diversity not being a part of Charles Tilly’s original theory and due to the non-significant results.

However, in later work by Wouters (2019), he looks at the dWUNC framework and the extent to which protest movements appeal to the general public, rather than legislators. He performs two studies - one looking at a demonstration for the rights of asylum seekers, and another looking at Black Lives Matter protests against police brutality, testing which features of each protest make a difference in the amount of support from the general public. In each study, the elements of the protest shown to respondents were manipulated to show varying levels of worthiness, unity, numbers, commitment, and diversity. Both studies found that diversity increased the support for the cause by statistically significant margins.

Specifically, Study 1 found the protest resonated more strongly when general citizens (4.82/10) rather than asylum seekers only participated (4.65/10). Study 2 found smaller effect sizes for diversity, for highs of 6.12 for diverse participants and 6 for a less diverse group. Relative to other dWUNC factors, diversity was considerably less important than worthiness (or nonviolence) but tied with unity as the second most important factor. The results from Study 2 are shown in the Figure below.

Figure 7. The interaction effect between diversity, worthiness and unity with support for police brutality demonstrators. Numbers and commitment are not shown here, due to finding no significant interaction effects, despite being tested. Source: Wouters (2019)

Chenoweth & Stephan (2011) studied over 300 movements fighting for regime change in authoritarian countries and also identified diversity of participants as a crucial factor in movement success. They argue that broad-based campaigns, that mobilise broad sectors of society, are much more likely to achieve wins; they threaten the legitimacy of the opponent, and carry greater costs for the government if they repress the movement. This research focuses on authoritarian regimes, so it is uncertain how these findings generalise to democratic contexts. Diverse participation in a democratic country is similarly likely to be more costly to the government in repressing the movement, so this finding seems to generalise. In addition, a democratic government should be more likely to make reforms if a movement is more diverse compared to a movement comprising a specific sector of society. Even a democratically elected government can reasonably ignore a single group, particularly if the group is unlikely to vote for their party. This becomes much more difficult for diverse and broad movements, where the participants are likely to represent potential voters.

7.2 Expert interviews

In our expert interviews around the most important factors for success (e.g. “What are the three most important factors for protest movements to succeed?”, there was no mention of diversity. We don’t think this means it's unimportant but it might be less important than other factors already mentioned.

7.3 Policymaker interviews

The interviews with three UK Civil Servants highlighted that policymakers believe diversity is one of the most important factors for a social movement organisation to influence policy. Specifically, all three civil servants raised the issue of diversity, and broadly thought it the second most important factor (after size). However, we believe the civil servants assumed nonviolence throughout our discussion, so it’s possible that diversity might actually be third with nonviolence placing slightly higher. As mentioned, the policymakers highlighted that an unexpected presence, such as school children who often don’t protest, can provide a stronger public opinion signal relative to “traditional” protestors.

Illustrative quotes:

-

“There was quite a bit of excitement about those protests, and with the school strike specifically it felt less political given it was children rather than trained political activists.”

-

“Diverse groups or movements are also a positive yet weak signal for public opinion, showing the issue is supported by a broader range of people rather than the usual suspects.”

-

“Otherwise, grassroots groups need to give sentiment that lots of people agree, or it has a very diverse backing to be compelling.”

8. Other potentially important factors

We examined, but found less evidence, on the following factors:

-

Unity

-

Commitment

-

Radical Flank effect

-

Trigger events

-

Intra-organisational factors (such as governance or team experience)

-

Protest frequency

-

Protest length

Due to there being comparatively little evidence regarding these factors, we are less confident here. While these factors might be harder to measure empirically and have been studied less, they are not necessarily less important. We present the available evidence below.

8.1 Commitment and Unity

Most of the compelling evidence we found for the unity or commitment of protesters impacting outcomes came from our literature review. However we are not convinced that there is sufficient evidence to make strong claims. The few studies indicating that either or both of these factors are relevant to success are outlined below:

-

Fassiotto and Soule (2017) find that ‘signal clarity’ (a proxy for ‘unity’) is associated with protest movements having an effect on legislators. Looking at marches relating to women’s rights in the United States, they operationalise ‘signal clarity’ in two ways: firstly, if women were reported as being the primary presence at a protest, and secondly, if the issues being espoused at protest events are similar over time. They find that both aspects of ‘signal clarity’ are strongly associated with at least one Congressional vote on Women’s issues in the subsequent month. It’s worth noting that this slightly contradicts claims around diversity, where several societal groups are seen as more compelling relative to a more uniform demographic bloc (e.g. all women).

-

Wouters and Walgrave (2017) conducted an experiment on Belgian legislators, and found that the unity of protesters had a significant impact on the position taken by legislators, the degree to which legislators believe the issue to be salient, and their view on whether they are likely to take action on it. ‘Unity’ is portrayed by the protesters showing a coherent message (such as holding the same signs, repetition of demands, etc.), whereas disunity is portrayed by showing diverging voices with different demands. The figure below shows the results.

Figure 8. The interaction effect between protestor unity and the likelihood of policymakers to consider a (protested) issue higher salience, take a position closer to that of the protestors' and their intention to take policy action on the protested issue. Source: Wouters and Walgrave (2017)

-

Wouters (2019) conducted an experiment looking at the impact of unity on the attitudes of members of the public. He found that when activists are portrayed as unified, members of the public are significantly more likely to say they agree with the protesters. The results are shown in the figure below.

Figure 9. The interaction effect between diversity, worthiness and unity and support from the general public for an asylum protest. Numbers and commitment are not shown since they showed no significant interaction effect. Source: Wouters (2019)

-

Wouters and Walgrave did not find a significant effect of commitment on any of the three measures (salience, position, and action), indicating that commitment may not have a strong impact on legislators. Commitment was operationalised by stating that further actions were planned (as opposed to no further action planned), and in the ‘low commitment’ condition, activists were shown smoking/drinking with their hands in their pockets rather than actively engaging in the protest.

-

Wouters (2019) similarly finds no impact of commitment on the attitudes of members of the public towards the issue being protested about.

8.2 Radical Flank Effect & Disruption

The ‘Radical Flank Effect’ (RFE) refers to the influence of a more radical faction of a social movement impacting support for moderate factions of the movement. This effect can be positive, whereby a radical faction can increase support for moderate factions, or negative, whereby support for moderate factions is decreased. There is some dispute about the extent to which the RFE is generally positive (referred to as the positive radical flank effect) or negative (referred to as the negative radical flank effect). Overall, we believe a violent radical flank is likely to have negative consequences overall, whilst a nonviolent radical flank may have positive consequences overall.

Arguments for the positive radical flank effect generally say that the existence of a radical flank makes the more moderate groups look better by comparison - for instance, peaceful animal rights advocates may benefit from being compared to activists perceived as more extreme or confrontational. By contrast, the negative radical flank effect would mean that moderates become associated with more radical groups and are tarnished by association. Radical flanks may also lead to increased state repression against the whole movement, leading to negative consequences for many more than just the group taking radical actions. The evidence in the literature on the RFE is mixed, making it unclear whether the RFE is more likely to be positive or negative. Additionally, most research focused on the radical flank effects looks at violent flanks within a primarily nonviolent movement. It does not yet offer much insight into radical yet nonviolent flanks within a primarily nonviolent movement. Literature relating to the RFE includes:

-

In an experimental study, Simpson et al. (2022) find that having a radical flank that uses radical tactics results in a more favourable impression of a more moderate flank, whereas a radical flank that has a radical ideology (but does not use more radical tactics) has no impact on the perception of the more moderate group. This seems to suggest that a radical flank with radical tactics may lead to more moderate groups being perceived more favourably, whereas a radical flank that merely has a radical agenda will have little or no impact on a more moderate group. The table below shows the results of the study:

Figure 10. The interaction effect between radical goals, radical tactics, and identification with and support for a more moderate faction for fictional groups within the animal advocacy movement. Source: Simpson et al. (2022)

-

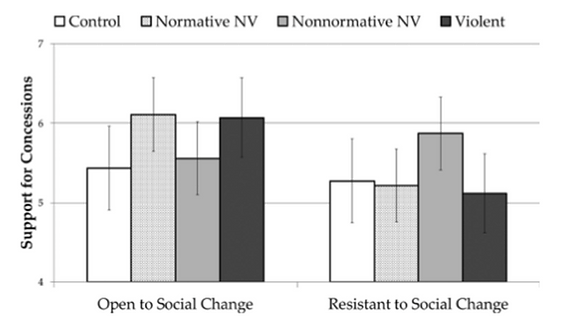

Shuman et al. (2020) finds that non-normative collective action, that is collective action that breaks social norms (potentially also viewed as disruptive or radical) may be effective in persuading those who are resistant to social change. In a series of five experimental studies, they test the impact of normative nonviolent action (e.g. peaceful protest), nonnormative nonviolent actions (e.g. blockades or sit-ins) and violent actions (e.g. riots and property destruction) against a control condition. They find that for people resistant to social change, nonnormative nonviolent action is more effective than the other forms of action (nothing, violence and normative nonviolent action) in increasing support for concessions.

Figure 11: Shuman et al. (2020) demonstrate the outcome of various forms of antiracist collective action for groups who are both open and resistant to social change. Resistance to social change for this experiment was defined as White racial identification (e.g. “I feel strong ties with other White Americans”).

-

Tompkins (2015) finds that having a violent radical flank within a primarily nonviolent movement is associated with more state repression, and is linked with decreased mobilisation. They also find that despite likely negative consequences on mobilisation, radical flanks had a modest association with increased likelihoods of campaign success. It’s worth noting this study was conducted using a subset of the NAVCO 2.0 dataset, which featured only nonviolent maximalist or regime-change campaigns from 1900 to 2016. As such, it may not generalise well to policy change campaigns in democratic countries.

-

Chenoweth & Stephan (2011) note that from 1900 to 2019, 65% of nonviolent campaigns without fringe violence succeeded in overthrowing regimes, but this was true of only 35% of movements with fringe violence. There is not much indication that this is a causal effect; it may simply be that unsuccessful groups are more likely to have radical fringes, even though the radical fringe has no causal effect on success.

8.3 Trigger Events and Protest Timing

In the words of Bill Moyer, Trigger events refer to “highly publicised, shocking incidents” that “dramatically reveal a critical social problem to the public in a vivid way.” Classic examples include the arrest of Rosa Parks in 1955 and the murder of George Floyd in 2020, both of which triggered a huge reaction from activists; Rosa Parks’ arrest leading to the Montgomery Bus Boycott and George Floyd’s murder leading to a wave of protest throughout the world.

We have not carried out an in-depth literature review of trigger events, but multiple experts we spoke to mentioned their importance.

Illustrative Quotes:

-

“Protests can make use of momentum to ensure that media coverage is sustained, and legislators respond to the increased attention on whatever the pertinent issue is. BLM was influential because the murder of George Floyd was a trigger event - there was an opportunity for them to have an impact on police departments in the US.”

-

“Protest groups should build the groundwork so that when an opportunity comes, they are able to grasp it. It is important for protesters to be ready for when they have a chance to build some momentum. The Spanish group Indignados had gatherings and collective identity-building to enable them to take action when opportunities arose.”

-

“We learned a lot from Serbian protesters about what are good predictors of a good core - having ‘hype people’ who know how to capitalise on a trigger event, and figuring out what actually constitutes a trigger event.”

-

“One important characteristic is ‘rapid response capacity’, people can temporarily become staff to help the mass protests. If people come and think this is a career for life, you can barely give any of those jobs for a mass protest movement. You need people who can drop out of whatever they’re doing and live on 30k for only a year - not people who want to earn 80k for ten years.”

It’s also worth noting that Vliegenthart et al. (2016) suggests that the most important factor in predicting whether a story is likely to receive media coverage is whether the story has already received media coverage. Therefore, protest movements may benefit from taking advantage of events that are already gaining media coverage.

8.4 Intra-organisational factors (e.g. governance, systems and team experience)

A common view expressed in our expert interviews, particularly amongst the social movement experts (rather than the academics), was that certain intra-organisational factors make some social movement organisations much more likely to succeed. Examples include levels of decentralisation, systemisation of work, clarity in policies, governance around decision-making, experience of the core team and internal team culture. Intra-organisational factors was the success factor mentioned most frequently in our expert interviews, and the one with the second largest number of unique experts who referenced it. However, just because a factor was mentioned more frequently, it does not necessarily mean the experts thought it was the most important factor.

Table 3: The top six success factors that our experts spoke about as being the most important factors for successful protest movements, in no particular order.

Despite these factors being mentioned frequently in our expert interviews, our other sources (literature review, policymaker interviews and case studies) revealed little on this particular question. Additionally, some of these factors, such as the health of an internal SMO culture, is challenging to measure empirically, and therefore hard to causally attribute success to. Due to this, we’re relatively uncertain about these factors, but we also think it’s notable that experts put significant weight on them.

8.4.1 Organisational systems and governance

Experts believe that factors such as having scalable systems to onboard volunteers, systems for healthy teamwork (e.g. resolving conflict, fair compensation, etc.) and the level of decentralisation play significant roles in the success of an SMO. However, there was some uncertainty about what level of decentralisation is optimal, and that this is likely to depend on the campaign and aims of the organisation. Experts also spoke about the necessity of understanding that an SMO needs to operate differently at different stages of its existence.

Select Quotes:

-

“[Successful SMOs] have systems in place. Designing big and scalable systems instead of doing things ad-hoc seems hugely important for movement success. They also need to have a healthy team - it’s possible for a team to add much more than the sum of its parts or to be much less effective than the sum of its parts, depending on how it is structured.”

-

“People often say that interpersonal dynamics are the most important factor in achieving a healthy team - in fact, the empirical evidence suggests that systems and structures are much more important.”

-

“‘Directed Network Campaigns’ have a central structure that works with grassroots groups on the outside of the campaign; this appears to be highly successful.”

-

“If you compare Black Lives Matter and protests during the Civil Rights Movement, it seems likely that the Civil Rights Movement benefited from having clearer leadership. Having a central figure makes it easier to identify with a social movement.”

-

“We don’t know how centralised a social movement or protest should be - some research suggests that bottom-up organisations seem to be more effective than having a centrally organised movement, but it isn’t definitive.”

8.4.2 Team experience and conflict

Interviewees said that organisers who had at least several years experience in SMOs, as well as teams with the ability to handle internal conflict, were much more likely to succeed relative to other groups. In addition, groups that had worked together previously, and even failed together, were likely to benefit most from the frontloading process, a process to design the strategy, narrative, structure and culture of a SMO before launching.

Select Quotes:

-

“Potentially most important is the make-up and experience of the core team [for an incubated social movement to do well].”

-

“The most successful cores had organisers who had been organising for at least ten years, but some of the cores only had people who had organised for one or two years”

-

“Sunrise [Movement] people all knew each other from the divestment movement. They all spoke in similar language and had all experienced failure together.”

-

“They also need to have a healthy team - it’s possible for a team to add much more than the sum of its parts or to be much less effective than the sum of its parts, depending on how it is structured.”

-

“A good core also needs to be able to deal with conflict well, many organisations fall apart when the conflict begins.”

-

“The thing that keeps people coming back to protests is if they had positive experiences with other people in their activist groups - activists would keep coming back to protests despite harsh crack-downs if the other protesters were committed and supportive.”

-

“People often say that interpersonal dynamics are the most important factor in achieving a healthy team - in fact, the empirical evidence suggests that systems and structures are much more important.”

8.5 Protest frequency and protest length

In addition to protest size (numbers), some studies indicate there might be a relationship between other protest variables, such as their frequency and duration.

8.5.1 Protest frequency

Walgrave and Vliegenthart (2012) examine protests between 1993 and 2000 in Belgium, looking at the impact of (mostly) nonviolent and legal protests on questions in parliament, decisions by government, and passed legislation. They found a significant impact of protest frequency on newspaper coverage of issues - the more frequent the protest, the more likely it is to be covered. The authors also looked specifically at New Social Movements (NSM) which Walgrave defines here, as concerning issues that are more global in scope, such as the environment, defence, and development, as opposed to more local issues (e.g. working conditions). They found that NSM protest frequency leads to an increase in Parliamentary debate and Ministerials decisions. By contrast, protest frequency did not have a significant effect on the passing of legislation. Walgrave and Vliegenthart used a large data-set of 3,839 demonstrations, 1,198 pieces of legislation and 180,265 news items, across 25 issues, which we think makes this piece of evidence fairly strong. Overall, the authors believe protest size is a more important factor in political agenda-setting and policy-shaping relative to protest frequency.

Figure 12: Identified causal relationships between protest size, media and legislation, from over 25 issues in Belgium from 1993 to 2000. NSM refers to “New Social Movement” which Walgrave defines here as issues that are more global in scope, such as environment, defence, and development. Source: Walgrave and Vliegenthart (2012)

Additionally, one policymaker, in our policymaker interviews, thought that protest frequency could be a signal of public opinion in much the same way as movement size can:

-

“Larger and more frequent protests provide much more compelling public opinion signals relative to small protests.”

8.5.1 Protest length

King and Soule (2007) fail to find any impact of protest size on chance of success, when considering the impact of protests against US corporations on the stock price of those same corporations between 1962 and 1990. They do find a significant negative correlation between the length of the protests and stock price - that is, the longer the protests went on, the more the stock price went down. They don’t provide much explanation of the potential mechanism besides this, except that longer protests may provoke a stronger reaction amongst investors relative to one-day protests.

9. Future work that could be promising

Given additional capacity, we would address key questions that might influence what we recommend to funders, decision-makers or movement leaders, such as:

-

What are some common reasons social movements or social movement organisations fail?

-

Literature review of the radical flank effect. A common claim by SMOs is that radical tactics work to increase support for more moderate groups, and for the issue overall. This is known as the radical flank effect.

-

Which factors most determine the success of social movements (rather than just protest movements)?

-

Which causes are the most suitable for a grassroots social movement, and which criteria should we use to determine this?

We are also interested in investigating whether grassroots movements can play an effective role in other issues, such as nuclear war, or other existential risks. We recognise the need to be cautious when researching the potential impact of protests on existential risks, due to the dangers that information hazards can pose.

10. Limitations

Besides the specific limitations of the individual research methodologies that we address in the respective reports, we believe there are broader limitations of our research:

-

Lack of evidence - Relative to our work on protest outcomes, we think the evidence base for success factors is relatively sparse. For some success factors, we were not able to find more than 3-5 academic studies meaning that we’re overall less confident in our findings for these factors.

-

Measurability bias - Some success factors are much easier to measure than others. For example, showing vignettes to the public with large protests versus small protests can be a good indicator of the importance of numbers, but it’s not clear how one would test the importance of internal team culture in the same way. As a result, we think the success factors above are biased towards more measurable factors, even though less measurable factors could theoretically be more important.

-

Protest movements are optimising for many different outcomes - Different organisations or movements might seek different outcomes (e.g. public opinion change, new policies, shifting public discourse) depending on their specific context. Some strategies might be more successful in progressing one particular outcome whilst being neutral, or even potentially harmful, for progressing another. As a result, it’s hard to confidently propose a generic list of success factors that will help an SMO or protest movement.

-

It’s unclear how much we can generalise - Most research related to protest has focused on the US and Western Europe. In addition, researchers tend to focus primarily on civil rights and environmentalism. It’s hard to accurately estimate how well these findings generalise to protests in other contexts - a different issue, country, political context or time period.

-

Causal inference is challenging - With most of our research, it is extremely challenging to draw watertight causal inferences between the protest or activities of the protest movement and the observed effects. This is especially true for observational studies, such as Chenoweth & Stephan (2011); it could be that, rather than large movements leading to a higher chance of success, it’s actually the public perceiving a higher chance of success that leads to more people joining a movement. Experimental studies are useful to determine causality, but suffer from poor external validity - that is, findings in controlled lab settings may not replicate in real-world settings due to large differences in context.

-

Long-term consequences are hard to evaluate - Whilst some factors, such as disruption, might be beneficial in the short-term to boost media attention, they might be damaging in the long-term (e.g. due to polarisation or repression). Since most studies are conducted over short-time periods or in an experimental setting, it’s unclear what the long-term consequences are.

-

Only the most influential movements are studied - Most of the literature on the impact of protests is likely to study protests perceived to have been particularly effective or otherwise noteworthy. Without a rigorous comparison of successful protest movements and failed protest movements, it’s unclear which specific factors increase or decrease the chance of success.

11. Conclusion

Overall, we find that several factors have a significant impact on the impact of a protest movement, namely nonviolence, large numbers and external context such as luck or political allies. We believe several other factors could potentially be very important, such as the radical flank effect, diversity, and intra-organisational factors such as team experience or culture, but there is comparatively much less evidence on these factors. We think this identifies a clear need for greater research into success factors, to help inform the strategy and campaigns of social movement organisations.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Markus Ostarek, Cathy Rogers, Carl Luthin for useful feedback and comments on this report- all errors are our own. An additional huge thank you to all the academics, movement leaders, researchers and policymakers whom we spoke to, who gave substantial time to help our work.

Appendix A - Methodology

A.1 Literature Review Methodology

The social science literature on protests and Social Movement Organisations (SMOs) is large. There is a substantial amount of theoretical literature and empirical literature, spanning political science, sociology, and other disciplines. We concentrated on newer, empirical research related to the following:

-

Modern, empirical research that used experimental or quasi-experimental methods, and had clear causal identification strategies.

-

Focused on countries similar to the contexts we are interested in, which is largely Western democracies (e.g. the UK, the US and countries in Western Europe). However, there was some useful research studying the overthrowing of autocratic regimes in the Global South (e.g. Stephan & Chenoweth, 2008), which we did include with some appropriate caveats.

-

Relatively recent protest movements, to provide more generalisability to the current social, political and economic contexts. Most papers we included were focused on movements from the 2000s onwards, or otherwise recent experimental studies.

-

We were less likely to include articles that were related to theoretical developments, our main focus was on empirical literature that was specifically looking at either the impact of protest, or the factors that affected the chance of protest success or failure.

-

We looked through both highly relevant journals (such as Mobilization and Social Forces) and top political science and sociology journals (such as APSR and ASR), as well as using tools like Elicit to find relevant research in other journals.

-

The characteristics of protests that make them more or less likely to be successful.

-

The political contexts in which protests are more or less likely to be successful.

When reviewing literature relating to factors that make protests more likely to be successful, we were particularly interested in research relating to Charles Tilley’s WUNC (Worthiness, Unity, Numbers, and Commitment) framework. As we were interested in understanding what can make protests more effective, the WUNC framework was a useful starting point for figuring out how the chance of success is affected by who protests and the way in which they protest, and how this can have an effect on the perceptions of both legislators and the general public. While there is not a huge amount of empirical work that explicitly references the WUNC framework (with the exception of the work of Ruud Wouters and Stefaan Walgrave), we prioritised other empirical research that seemed to fit into the WUNC Framework - for instance, Fassiotto and Soule’s work on ‘Signal Clarity’, which seems directly related to the ‘Unity’ element of the WUNC framework. That being said, we did examine some of the literature on how political context and political opportunity can impact the chance of success for protests and SMOs.

Search Methods